Weight Sharing

The simplest form of network reduction involves sharing weights between layers or structures within layers (e.g filters in CNNs). We note that unlike compression techniques discussed in later sections (Section 3-6), standard weight sharing is carried out prior to training the original networks as opposed to compressing the model after training. However,recent work which we discuss here~\citep{chen2015compressing,ullrich2017soft,bai2019deep} have also been used to reduce DNNs post-training and hence we devote this section to this straightforward and commonly used technique.

Weight sharing reduces the network size and avoids sparsity. It is not always clear how many and what group of weights should be shared before there is an unacceptable performance degradation for a given network architecture and task. For example,~\citet{inan2016tying} find that tying the input and output representations of words leads to good performance while dramatically reducing the number of parameters proportional to the size of the vocabulary of given text corpus. Although, this may be specific to language modelling, since the output classes are a direct function of the inputs which are typically very high dimensional (e.g typically greater than \(10^6\)). Moreover, this approach assigns the embedding matrix to be shared, as opposed to sharing individual or sub-blocks of the matrix. Other approaches include clustering weights such that their centroid is shared among each cluster and using weight penalty term in the objective to group weights in a way that makes them more amenable to weight sharing. We discuss these approaches below along with other recent techniques that have shown promising results when used in DNNs.

% However, \(\ell_2\) regularization can force large weights away from values required to fit the data well while two weights which are highly correlated and close to 0 are more favorable even though these weight pair may carry out the same purpose as a single large weight. Therefore,

\subsection{Clustering-based Weight Sharing} ~\citet{nowlan1992simplifying} instead propose a soft weight sharing scheme by learning a Gaussian Mixture Model that assigns groups of weights to a shared value given by the mixture model. By using a mixture of Gaussians, weights with high magnitudes that are centered around a broad Gaussian component are under less pressure and thus penalized less. In other words, a Gaussian that is assigned for a subset of parameters will force those weights together with lower variance and therefore assign higher probability density to each parameter.

\autoref{eq:gmm_cost} shows the cost function for the Gaussian mixture model where \(p(w_j)\) is the probability density of a Gaussian component with mean \(\mu_j\) and standard deviation \(\sigma_j\). Gradient Descent is used to optimize \(w_i\) and mixture parameters \(\pi_j\), \(\mu_j\), \(\sigma_j\) and \(\sigma_y\).

\begin{equation}\label{eq:gmm_cost} C = \frac{K}{\sigma^2_y} \sum_c (y_c - d_c)^2 - \sum_i \log \Big[\sum_j \pi_j p_j (w_i)\Big] \end{equation}

The expectation maximization (EM) algorithm is used to optimize these mixture parameters. The number of parameters tied is then proportional to the number of mixture components that are used in the Gaussian model.

\paragraph{An Extension of Soft-Weight Sharing} ~\citet{ullrich2017soft} build on soft-weight sharing~\citep{nowlan1992simplifying} with factorized posteriors by optimizing the objective in \autoref{eq:var_compress}. Here, \(\tau=5e^{-3}\) controls the influence of the log-prior means \(\mu\), variances \(\sigma\) and mixture coefficients \(\pi\), which are learned during retraining apart from the j-th component that are set to \(\mu_j=0\) and \(\pi_j=0.99\). Each mixture parameter has a learning rate set to \(5 \times 10^{-4}\). Given the sensitivity of the mixtures to collapsing if the correct hyperparameters are not chosen, they also consider the inverse-gamma hyperprior for the mixture variances that is more stable during training.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:var_compress} \mathcal{L}\big(w,{\mu_j,\sigma_j,\pi_j }{j=0}^J \big) =\mathcal{L}_E + \tau \mathcal{L}_C = - \log p \big(\tau| X, w \big) - \tau \log p\big(w,{\mu_j,\sigma_j, \pi_j }{j=0}^J \big) \end{equation}

After training with the above objective, if the components have a KL-divergence under a set threshold, some of these components are merged~\citep{adhikari2012multiresolution} as shown in \autoref{eq:kl_merge}. Each weight is set then set to the mean of the component with the highest mixture value \(\argmax(\pi)\), performing GMM-based quantization.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:kl_merge} \pi_{\text{new}} = \pi_i + \pi_j,\quad \mu_{\text{new}} = \frac{\pi_i \mu_i+\pi_j \mu_j}{\pi_i+\pi_j},\quad \sigma^2_{\text{new}}= \frac{\pi_i\sigma^2_i+\pi_j \sigma^2_j}{\pi_i+\pi_j} \end{equation}

In their experiments, 17 Gaussian components were merge to 6 quantization components, while still leading to performance close to the original LeNet classifier used on MNIST.

%The network initially begins with 17 Gaussian components with broad variance and during learning, pairs of these components are merged resulting in 6 components with relatively narrower variance and higher concentration around the mean. These components are then used for quantization.

\subsection{Learning Weight Sharing} ~\citet{zhang2018learning} explicitly try to learn which weights should be shared by imposing a group order weighted \(\ell_1\) (GrOWL) sparsity regularization term while simultaneously learning to group weights and assign them a shared value. In a given compression step, groups of parameters are identified for weight sharing using the aforementioned sparsity constraint and then the DNN is retrained to fine-tune the structure found via weight sharing. GrOWL first identify the most important weights and then clusters correlated features to learn the values of the closest important weight throughout training. This can be considered an adaptive weight sharing technique.

~\citet{plummer2020shapeshifter} learn what parameters groupings to share and can be shared for layers of different size and features of different modality. They find parameter sharing with distillation further improves performance for image classification, image-sentence retrieval and phrase grounding.

\paragraph{Parameter Hashing} ~\citet{chen2015compressing} use hash functions to randomly group weight connections into hash buckets that all share the same weight value. Parameter hashing~\citep{weinberger2009feature,shi2009hash} can easily be used with backpropogation whereby each bucket parameters have subsets of weights that are randomly i.e each weight matrix contains multiple weights of the same value (referred to as a \textit{virtual matrix}), unlike standard weight sharing where all weights in a matrix are shared between layers.

\subsection{Weight Sharing in Large Architectures} \paragraph{Applications in Transformers} \citet{dehghani2018universal} propose Universal Transformers (UT) to combine the benefits of recurrent neural networks~\citep[(RNNs)][]{rumelhart1985learning,hochreiter1997long} (recurrent inductive bias) with Transformers~\citep{vaswani2017attention} (parallelizable self-attention and its global receptive field). As apart of UT, weight sharing to reduce the network size showed strong results on NLP defacto benchmarks while .

~\citet{dabre2019recurrent} use a 6-hidden layer Transformer network for neural machine translation (NMT) where the same weights are fed back into the same attention block recurrently. This straightforward approach surprisingly showed similar performance of an untied 6-hidden layer for standard NMT benchmark datasets.

% to reduce the number of parameters and ~\citet{xiao2019sharing} use shared attention weights in Transformer as dot-product attention can be slow during the auto-regressive decoding stage. Attention weights from hidden states are shared among adjacent layers, drastically reducing the number of parameters proportional to number of attention heads used. The Jenson-Shannon (JS) divergence is taken between self-attention weights of different heads and they average them to compute the average JS score. They find that the weight distribution is similar for layers 2-6 but larger variance is found among encoder-decoder attention although some adjacent layers still exhibit relatively JS score. Weight matrices are shared based on the JS score whereby layers that have JS score larger than a learned threshold (dynamically updated throughout training) are shared. The criterion used involves finding the largest group of attention blocks that have similarity above the learned threshold to maximize largest number of weight groups that can be shared while maintaining performance. They find a 16 time storage reduction over the original Transformer while maintaining competitive performance.

%\paragraph{Weight Agnostic Neural Networks} ~\citet{gaier2019weight} \paragraph{Deep Equilibrium Model} ~\citet{bai2019deep} propose deep equilibrium models (DEMs) that use a root-finding method to find the equilibrium point of a network and can be analytically backpropogated through at the equilibrium point using implicit differentiation. This is motivated by the observation that hidden states of sequential models converge towards a fixed point. Regardless of the network depth, the approach only requires constant memory because backpropogration only needs to be performed on the layer of the equilibrium point.

For a recurrent network \(f_{\mat{W}}(\vec{z}^*_{1:T};\vec{x}_{1:T})\) of infinite hidden layer depth that takes inputs \(\vec{x}_{1:T}\) and hidden states \(\vec{z}_{1:T}\) up to \(T\) timesteps, the transformations can be expressed as,

\begin{equation} \lim_{i \to \infty} z_{1:T}^{[i]} = \lim_{i \to \infty} f_{W} (\vec{Z}{1:T}^{[i]}; \vec{x}{1:T}) := f_{W}(\vec{z}^_{1:T}; x_{1:T}) = \underbrace{\vec{z}^{1:T}}{\text{equilibrium point}} \end{equation}

where the final representation \(\vec{z}^*_{1:T}\) is the hidden state output corresponds to the equilibrium point of the network. They assume that this equilibrium point exists for large models, such as Transformer and Trellis~\citep{bai2018trellis} networks (CNN-based architecture).

The \(\frac{\partial \vec{z}^*_{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}}\) requires implicit differentiation and \autoref{eq:deq_2} can be rewritten as \autoref{eq:deq_3}.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:deq_2} \frac{\partial \vec{z}^_{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}} = \frac{d f_{W}(\vec{z}^{1:T}; \vec{x}{1:T})}{d \mat{W}} + \frac{\partial f_{W}(\vec{z}^_{1:T}; \vec{x}_{1:T})}{\partial \vec{z}^{1:T}} \frac{\partial \vec{z}^*{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\label{eq:deq_3} \Big(I - \frac{\partial f_{W}(\vec{z}^_{1:T}; \vec{x}_{1:T})}{\partial \vec{z}^{1:T}} \Big) \frac{\partial \vec{z}^*{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}} = \frac{d f_{W}(\vec{z}^*{1:T}; \vec{x}{1:T})}{d\ \mat{W}} \end{equation}

For notational convenience they define \(g_{\mat{W}}(z^{*}_{1:T}; \vec{x}_{1:T}) =f_{\mat{W}}(z^{*}_{1:T}; \vec{x}_{1:T}) - \vec{z}^{*}_{1:T} \to 0\) and thus the equilibrium state \(\vec{z}^{*}_{1:T}\) is thus the root of \(g_{\mat{W}}\) found by the Broyden's method~\citep{broyden1965class}\footnote{A quasi-Newton method for finding roots of a parametric model.}.

The Jacobian of the function \(g_{\mat{W}}\) at the equilibrium point \(\vec{z}^*_{1:T}\) w.r.t \(\mat{W}\) can then be expressed as \autoref{eq:deq_5}. Note that this is computed without having to consider how the equilibrium \(\vec{z}^*_{1:T}\) was obtained.

\begin{equation}\label{eq:deq_5} \mat{J}{g\mat{W}}\Big|{\vec{z}^*{1:T}} = - \Big(I - \frac{\partial f_{W}(\vec{z}^_{1:T}; \vec{x}_{1:T})}{\partial \vec{z}^_{1:T}} \Big) \end{equation}

Since \(f_{\mat{W}}(\cdot)\) is in equilibrium at \(\vec{z}^*_{1:T}\) they do not require to backpropogate through all the layers, assuming all layers are the same (this is why it is considered a weight sharing technique). They only need to solve \autoref{eq:deq_6} to find the equilibrium points using Broydens method,

\begin{equation}\label{eq:deq_6} \frac{\partial \vec{z}^{}_{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}} = - \mat{J}_{g_\mat{W}}\Big|_{\vec{z}^{1:T}} \frac{d\ f{\mat{W}}(\vec{z}^*{1:T}; \vec{x}{1:T})}{d \mat{W}} \end{equation}

and then perform a single layer update using backpropogation at the equilibrium point. \begin{equation}\label{eq:dem_7} \frac{\partial \cL}{\partial \mat{W}} = \frac{\cL}{\partial \vec{z}^_{1:T}} \frac{\partial \vec{z}^{1:T}}{\partial \mat{W}} = - \frac{\partial \cL}{\partial \vec{z}^*{1:T}\Big(\mat{J}^{-1}{g\mat{W}}\big|{\vec{z}^*{1:T}}\Big)} \frac{d\ f_{\mat{W}}(\vec{z}^*{1:T}; \vec{x}{1:T})}{d \mat{W}} \end{equation}

The benefit of using Broyden method is that the full Jacobian does not need to be stored but instead an approximation \(\hat{\mat{J}}^{-1}\) using the Sherman-Morrison formula~\citep{scellier2017equilibrium} which can then be used as apart of the Broyden iteration:

\begin{equation} \vec{z}{1:T}^{[i+1]} := \vec{z}{1:T}^{[i]} - \alpha \hat{\mat{J}}^{-1}{g\mat{W}}\Big|{\vec{z}{1:T}^{[i]}} g_{\mat{W}}(\vec{z}{1:T}^{[i]}; \vec{x}{1:T}) \quad \text{for} \quad i = 0, 1, 2, \ldots \end{equation}

where \(alpha\) is the learning rate. This update can then be expressed as \autoref{eq:dem_8}

\begin{equation}\label{eq:dem_8} \mat{W}^+ = \mat{W} - \alpha \cdot \frac{\partial \cL}{\partial \mat{W}} = \mat{W} + \alpha \frac{\partial \cL}{\partial \vec{z}_{1:T}\Big(\mat{J}^{-1}_{g_\mat{W}}\big|_{\vec{z}^{}{1:T}}\Big)} \frac{d\ f{\mat{W}}(\vec{z}^{*}{1:T}; \vec{x}{1:T})}{d \mat{W}} \end{equation}

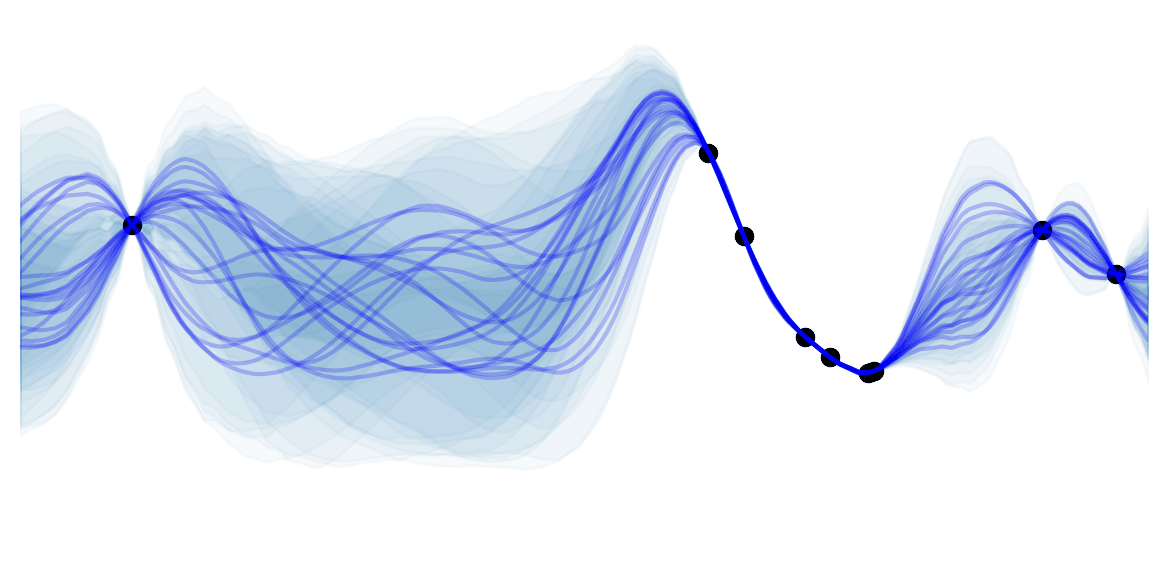

\autoref{fig:dem} shows the difference between a standard Transformer network forward pass and backward pass in comparison to DEM passes. The left figure illustrates the Broyden iterations to find the equilibrium point for inputs over successive inputs. On WikiText-103, they show that DEMs can improve SoTA sequence models and reduce memory by 88\% use for similar computational requirements as the original models.

\begin{figure} \centering \includegraphics[scale=0.38]{images/deq_weight_sharing.png} \caption{original source~\citet{bai2019deep}: Comparison of the DEQ with conventional weight-tied deep networks} \label{fig:dem} \end{figure}

\subsection{Reusing Layers Recursively} Recursively re-using layers is another form of parameter sharing. This involves feeding the output of a layer back into its input.

~\citet{eigen2013understanding} have used recursive layers in CNNs and analyse the effects of varying the number of layers, features maps and parameters independently. They find that increasing the number of layers and number of parameters are the most significant factors while increasing the number of feature maps (i.e the representation dimensionality) improves as a byproduct of the increase in parameters. From this, they conclude that adding layers without increasing the number of parameters can increase performance and that the number of parameters far outweights the feature map dimensions with respect to performance.

~\citet{kopuklu2019convolutional} have also focused on reusing convolutional layers using recurrency applying batch normalization after recursed layers and channel shuffling to allow filter outputs to be passed as inputs to other filters in the same block. By channel shuffling, the LRU blocks become robust with dealing with more than one type of channel, leading to improved performance without increasing the number of parameters. ~\citet{savarese2019learning} learn a linear combination of parameters from an external group of templates. They too use recursive convolutional blocks as apart of the learned parameter shared weighting scheme.

However, layer recursion can lead to \textit{vanishing or exploding gradients} (VEGs). Hence, we concisely describe previous work that have aimed to mitigate VEGs in parameter shared networks, namely ones which use the aforementioned recursivity.

%The use of \textit{skip connections}, which were introduced in Residual networks~\cite{he2016deep}, can be used to ameliorate gradient vanishing in parameter shared networks. Alternatively,

~\citet{kim2016deeply} have used residual connections between the input and the output reconstruction layer to avoid signal attenuation, which can further lead to vanishing gradients in the backward pass. This is applied in the context self-supervision by reconstructing high resolution images for image super-resolution. % itet{sperduti1997supervised} (see figure 8 in their paper) ~\citet{tai2017image} extend the work of~\citet{kim2016deeply}. Instead of passing the intermediate outputs of a shared parameter recursive block to another convolutional layer, they use an elementwise addition of the intermediate outputs of the residual recursive blocks before passing to the final convolutional layer. The original input image is then added to the output of last convolutional layer which corresponds to the final representation of the recursive residual block outputs.

~\citet{zhang2018residual} combine residual (skip) connections and dense connections, where skip connections add the input to each intermediate hidden layer input.

~\cite{guo2019dynamic} address VGs in recursive convolutional blocks by using a gating unit that chooses the number of self-loops for a given block before VEGs occur. They use the Gumbel Softmax trick without gumbel noise to make deterministic predictions of the number of self-loops there should be for a given recursive block throughout training. They also find that batch normalization is at the root of gradient explosion because of the statistical bias induced by having a different number of self-loops during training, effecting the calculation of the moving average. This is adressed by normalizing inputs according to the number of self-loops which is dependent on the gating unit. When used in Resnet-53 architecture, dynamically recursivity outperforms the larger ResNet-101 while reducing the number parameters by 47\%.