Pruning

Pruning weights is perhaps the most commonly used technique to reduce the number of parameters in a pretrained DNN. Pruning can lead to a reduction of storage and model runtime and performance is usually maintaining by retraining the pruned network. Iterative weight pruning prunes while retraining until the desired network size and accuracy tradeoff is met. From a neuroscience perspective, it has been found that as humans learn they also carry out a similar kind of iterative pruning, removing irrelevant or unimportant information from past experiences ~\citep{walsh2013peter}. Similarly, pruning is not carried out at random, but selected so that unimportant information about past experiences is discarded. In the context of DNNs, random pruning (akin to Binary Dropout) can be detrimental to the models performance and may require even more retraining steps to account for the removal of important weights or neurons~\citep{yu2018nisp}.

The simplest pruning strategy involves setting a threshold \(\gamma\) that decides which weights or units (in this case, the absolute sum of magnitudes of incoming weights) are removed~\citep{hagiwara1994removal}. The threshold can be set based on each layers weight magnitude distribution, where weights centered around the mean \(\mu\) are removed, or it the threshold can be set globally for the whole network. Alternatively, pruning the weights with lowest absolute value of the normalized gradient multiplied by the weight magnitude~\citep{lee2018snip} for a given set of mini-batch inputs can be used, either layer-wise or globally too.

Instead of setting a threshold, one can predefine a percentage of weights to be pruned based on the magnitude of \(w\), or a percentage aggregated by weights for each layer \(w_{l},\ \forall l \in L\). Most commonly, the percentage of weights that are closest to 0 are removed. The aforementioned criteria for pruning are all types of \textit{magnitude-based pruning} (MBP). MBP has also been combined with other strategies such as adding new neurons during iterative pruning to further improve performance~\citep{han2013structure,narasimha2008integrated}, where the number of new neurons added is less than the number pruned in the previous pruning step and so the overall number of parameters monotonically decreases.

MBP is the most commonly used in DNNs due to its simplicity and performs well for a wide class of machine learning models (including DNNs) on a diverse range of tasks~\citep{setiono2000pruned}. In general, global MBP tends to outperform layer-wise MBP~\citep{karnin1990simple,reed1993pruning,hagiwara1994removal,lee2018snip}, because there is more flexibility on the amount of sparsity for each layer, allowing more salient layer to be more dense while less salient to contain more non-zero entries. Before discussing more involved pruning methods, we first make some important categorical distinctions.

Categorizing Pruning Techniques}

Pruning algorithms can be categorized into those that carry out pruning without retraining the pruning and those that do. Retraining is often required when pruning degrades performance. This can happen when the DNN is not necessarily overparameterized, in which case almost all parameters are necessary to maintain good generalization.

Pruning techniques can also be categorized into what type of criteria is used as follows:

- The aforementioned magnitude-based pruning whereby the weights with the lowest absolute value of the weight are removed based on a set threshold or percentage, layer-wise or globally.

- Methods that penalize the objective with a regularization term to force the model to learn a network with (e.g $\ell_1$, $\ell_2$$or lasso weight regularization) smaller weights and prune the smallest weights.

- Methods that compute the sensitivity of the loss function when weights are removed and remove the weights that result in the smallest change in loss.

- Search-based approaches (e.g particle filters, evolutionary algorithms, reinforcement learning) that seek to learn or adapt a set of weights to links or paths within the neural network and keep those which are salient for the task. Unlike (1) and (2), the pruning technique does not involve gradient descent as apart of the pruning criteria (with the exception of using deep RL).

Unstructured vs Structured Pruning

Another important distinction to be made is that between structured and unstructured pruning techniques where the latter aims to preserve network density for computational efficiency (faster computation at the expense of less flexibility) by removing groups of weights, whereas unstructured is unconstrained to which weights or activations are removed but the sparsity means that the dimensionality of the layers does not change. Hence, sparsity in unstructured pruning techniques provide good performance at the expense of slower computation. For example, MBP produces a sparse network that requires sparse matrix multiplication (SMP) libraries to take full advantage of the memory reduction and speed benefits for inference. However, SMP is generally slower than dense matrix multiplication and therefore there has been work towards preserving subnetworks which omit the need for SMP libraries (discussed in \autoref{sec:struct_prune}).

With these categorical distinctions we now move on to the following subsections that describe various pruning approaches beginning with pruning by using weight regularization.

Pruning using Weight Regularization

Constraining the weights to be close to 0 in the objective function by adding a penalty term and deleting the weights closest to 0 post-training can be a straightforward yet effective pruning approach. ~\autoref{eq:penalty_term_1} shows the commonly used \(\ell_2\)penalty that penalizes large weights \(w_m\) in the \(m\)-th hidden layer with a large magnitude and \(\vec{v}_m\) are the output layer weights of output dimension \(C\).

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:penalty_term_1} C(\vec{w}, \vec{v}) = \frac{\epsilon}{2} \Big(\sum_{m=1}^{h}\sum_{l=1}^n \vec{w}^2_{m l} + \sum_{m=1}^{h}\sum_{p=1}^C \vec{v}^2_{pm}\Big) \end{equation}\]However, the main issue with using the above quadratic penalty is that all parameters decay exponentially at the same rate and disproportionately penalizes larger weights. Therefore,~\citet{weigend1991generalization} proposed the objective shown in \autoref{eq:weig}. When \(f(w):= w^2/(1 + w^2)\) this penalty term is small and when large it tends to 1. Therefore, these terms can be considered as approximating the number of non-zero parameters in the network.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:weig} C(\vec{w}, \vec{v}) = \frac{\epsilon}{2} \Big(\sum_{m=1}^{h}\sum_{l=1}^n \frac{\vec{w}^2_{ml}}{ 1 +\vec{w}^2_{ml}} + \sum_{m=1}^{h} \sum_{p=1}^C \frac{\vec{v}^2_{pm}}{ 1 + \vec{v}^2_{pm}}\Big) \end{equation}\]The derivative \(f'(w) = 2\vec{w}/(1 + \vec{w}^2)^2\) computed during backprogation does not penalize large weights as much as \autoref{eq:penalty_term_1}. However, in the context of recent years where large overparameterized network have shown better generalization when the weights are close to 0, we conjecture that perhaps \autoref{eq:weig} is more useful in the underparameterized regime. The $\epsilon$$controls how the small weights decay faster than large weights. However, the problem of not distinguishing between large weights and very large weights is also an issue. Therefore, ~\citet{weigend1991generalization} further propose the objective in \autoref{eq:penalty_term_3}.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:penalty_term_3} C(\vec{w}, \vec{v}) = \epsilon_1 \sum_{m=1}^{h} \Big(\sum_{l=1}^n \frac{\beta \vec{w}^2_{ml}}{ 1 + \beta \vec{w}^2_{ml}} + \sum_{p=1}^C \frac{\beta \vec{v}^2_{pm}}{ 1 + \beta \vec{v}^2_{pm}}\Big) + \epsilon_2 \sum_{m=1}^h \Big(\sum_{l=1}^n \vec{w}^2_{ml} + \sum_{p=1}^C \vec{v}_{pm}^2 \Big) \end{equation}\]~\citet{wan2009enhancing} have proposed a Gram-Schmidth (GS) based variant of backpropogation whereby GS determines which weights are updated and which ones remain frozen at each epoch.

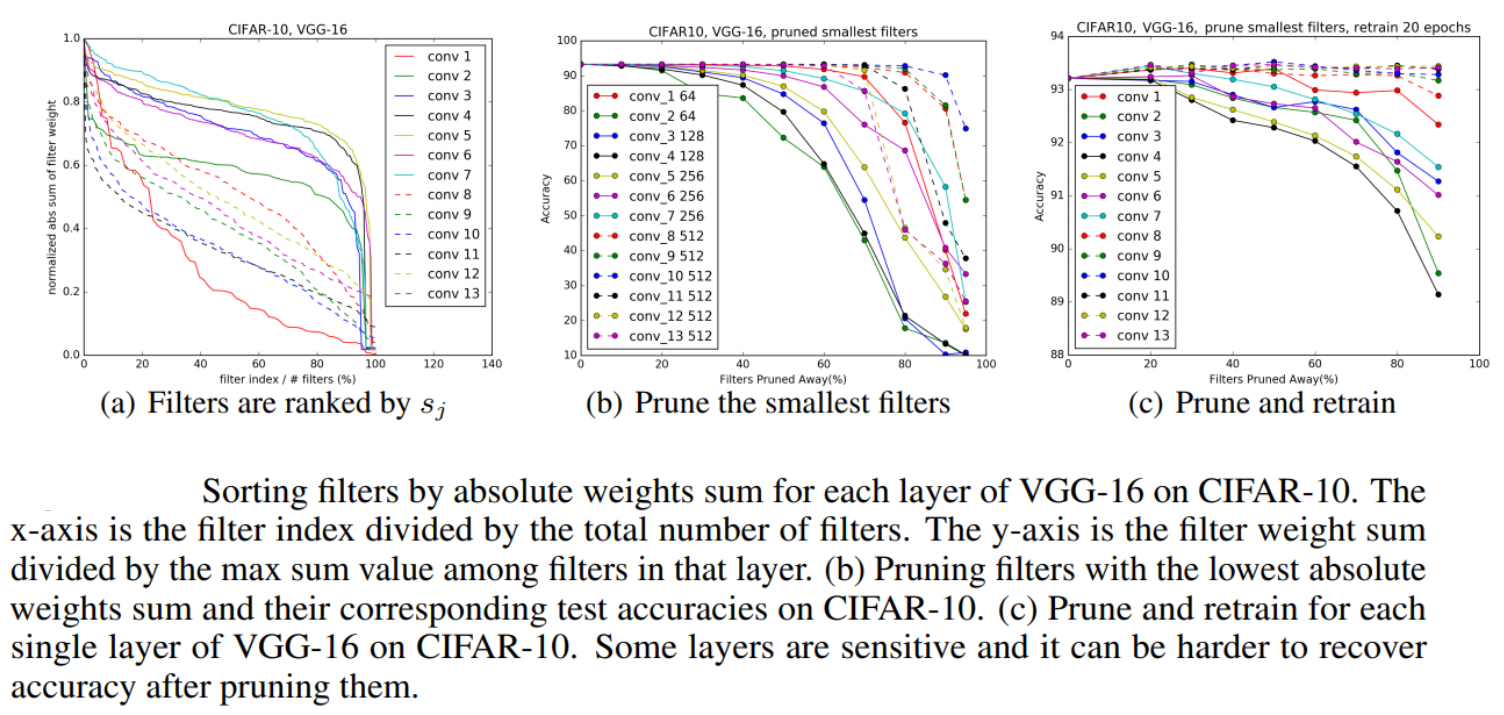

~\citet{li2016pruning} prune filters in CNNs by identifying filters which contribute least to the overall accuracy. For a given layer, sum of the weight magnitudes are computed and since the number of channels is the same across filters, this quantity represents the average of weight value for each kernel. Kernels with weights that have small weight activations will have weak activation and hence these will be pruned. This simple approach leads to less sparse connections and leads to 37\% accuracy reduction on average across the models tested while still being close to the original accuracy.~\autoref{fig:rank_pruned_cnn_filters} shows their figure that demonstrates that pruning filters that have the lowest sum of weight magnitudes correspond to the best maintaining of accuracy.

Pruning via Loss Sensitivity

Networks can also be pruned by measuring the importance of weights or units by quantifying the change in loss when a weight or unit is removed and prune those which cause the least change in the loss. Many methods from previous decades have been proposed based on this principle ~\citep{reed1993pruning,lecun1990optimal,hassibi1994optimal}. We briefly describe each one below in chronological order.

Skeletonization}

~\citet{mozer1989skeletonization} estimate which units are least important and deletes them during training. The method is referred to as skeletonization, since it only keeps the units which preserve the main structure of the network that is required for maintaining good out-of-sample performance. Each weight \(w\) in the network is assigned an importance weight \(\alpha\) where \(alpha=0\) the weight becomes redundant and \(\alpha=1\) the weight acts as a standard hidden unit.

To obtain the importance weight for a unit, they calculate the loss derivative with respect to \(\alpha\) as \(\hat{\rho}_i = \partial \mathcal{L} / {\alpha_i}\big|_{\alpha_i = 1}\) where \(\mathcal{L}\) in this context is the sum of squared errors. Units are then pruned when \(\hat{\rho}_i\) falls below a set threshold. However, they find that \(\hat{\rho}_i\) can fluctuate throughout training and so they propose an exponentially-decayed moving average over time to smoothen the volatile gradient and also provide better estimates when the squared error is very small. This moving average is given as,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:fluct_sens} \hat{\rho}_i(t + 1) = \beta \hat{\rho}_i(t) + (1 - \beta) \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}(t)}{\alpha_i} \end{equation}\]where \(\beta = 0.8\) in their experiments. Applying skeletonization to current DNNs is perhaps be too slow to compute as it was originally introduced in the context of using neural networks with a relatively small amount of parameters. However, assigning importance weights for groups of weights, such as filters in a CNN is feasible and aligns with current literature~\citep{wen2016learning,anwar2017structured} on structured pruning (discussed in ~\autoref{sec:struct_prune}).

Pruning Weights with Low Sensitivity

~\citet{karnin1990simple} measure the sensitivity \(S\) of the loss function with respect to weights and prune weights with low sensitivity. Instead of removing each weight individually, they approximate \(S\) by the sum of changes experienced by the weight during training as

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:simple_sensitivity_2} S_{ij} = \Big|- \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L} }{\partial \vec{w}_{ij}}\Delta \vec{w}_{ij}(n) \frac{\vec{w}^f_{ij}}{\vec{w}^f_{ij} - \vec{w}^i_{ij}} \Big| \end{equation}\]where \(w^f\) is the final weight value at each pruning step, \(w^i\) is the initial weight after the previous pruning step and $N\(is the number of training epochs. Using backpropagation to compute\)\Delta w$, $\hat{S}_{ij}$$ is expressed as,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:simple_sensitivity_3} \hat{S}_{ij} = \Big|- \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}\big\[\Delta \vec{w}_{ij}(n)\big]^2 \frac{\vec{w}^f_{ij}}{\nabla (\vec{w}^f_{ij} - \vec{w}^i_{ij})} \Big| \end{equation}\]If the sum of squared errors is less than that of the previous pruning step and if a weight in a hidden layer with the smallest \(S_{ij}\) changes less than the previous epoch, then these weights are pruned. This is to ensure that weight with small initial sensitivity are not pruned too early, as they may perform well given more retraining steps. If all incoming weights are removed to a unit, the unit is also removed, thus, removing all outgoing weights from that unit. Lastly, they lower bound the number of weights that can be pruned for each hidden layer, therefore, towards the end of training there may be weights with low sensitivity that remain in the network.

Variance Analysis on Sensitivity-based Pruning

~\citet{engelbrecht2001new} remove weights if its variance in sensitivity is not significantly different from zero. If the variance in parameter sensitivities is not significantly different from zero and the average sensitivity is small, it indicates that the corresponding parameter has little or no effect on the output of the NN over all patterns considered. A hypothesis testing step then uses these variance nullity measures to statistically test if a parameter should be pruned, using the distribution.What needs to be done is to test if the expected value of the sensitivity of a parameter over all patterns is equal to zero. The expectation can be written as \(\mathcal{H}_0: \langle S_{oW, ki} \rangle^2 = 0\) where \(S_{oW}\)is the sensitivity matrix of the output vector with respect to the parameter vector $\vec{W}\(and individual elements\)S_{oW, ki}\(refers to the sensitivity of output to perturbations in parameter over all samples. If the hypothesis is accepted, prune the corresponding weight at the\)(k, i)\(position, otherwise check\)\mathcal{H}0: \text{var}(S{oW, ki}) = 0$$ and if this accepted also opt to prune it. They test sum-norm, Euclidean-norm and maximum-norm to compute the output sensitivity matrix. They find that this scheme finds smaller networks than OBD, OBS and standard magnitude-based pruning while maintaining the same accuracy on multi-class classification tasks.

~\citet{lauret2006node} use a Fourier decomposition of the variance of the model predictions and rank hidden units according to how much that unit accounts for the variance and eliminates based on this variance-based spectral criterion. For a range of variation $[a_h, b_h]\(of parameter $w_h\)of layer $h\(and $N\)number of training iterations, each weight is varied as \(w_h^{(n)} = (b_h + a_h / 2) + (b_h - a_h/2)\sin(\omega_h s^(n))\) where \(s^{(n)} = 2\pi n/N\) and \(\omega_h\) is the frequency of $w_h\(and $n\)is the training iteration. The \(s_h\) is then obtained by computing the Fourier amplitudes of the fundamental frequency \(\omega_h\), the first harmonic up to the third harmonic.

Pruning using Second Order Derivatives

Optimal Brain Damage

As mentioned, deleting single weights is computationally inefficient and slow.~\citet{lecun1990optimal} instead estimate weight importance by making a local approximation of the loss with a Taylor series and use the $2^{nd}$$derivative of the loss with respect to the weight as a criterion to perform a type of weight sharing constraint. The objective is expressed as \autoref{eq:obd}

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:obd} \delta \mathcal{L} = \sum_i \cancelto{0}{g_i \delta \breve{w}_i} + \frac{1}{2} \sum_i h_{ii} \delta \breve{w}^2_i + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i \neq j} h_{ij} \delta \breve{w}_i \delta w_j + \cancelto{0}{O(||\breve{W}||^2)} \end{equation}\]where \(\breve{w}\) are perturbed weights of \(w\), the \(\delta \breve{w}_i\)'s are the components of \(\delta \breve{W}\), \(g_i\) are the components of the gradient \(\partial \mathcal{L} / \partial \breve{w}_i\) and \(h_{ij}\) are the elements of the Hessian \(\mathbf{H}\)where $\mathbf{H}{ij} := \partial^2 \mathcal{L}/\partial \breve{w}_i \partial \breve{w}_j\(. Since most well-trained networks will have\)\mathcal{L} \approx 0$, the $1^{st}\(term is\)\approx 0\(. Assuming the perturbations on\)W\(are small then the last term will also be small and hence ~\citet{lecun1990optimal} assume the off-diagonal values of\)\mathbf{H}\(are\)0\(and hence\)1/2\sum{i \neq j} h_{ij} \delta \breve{w}_i \delta w_j := 0\(. Therefore,\)\delta \mathcal{L}$$is expressed as,

\[\begin{equation} \delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i} h_{ii} \delta \breve{w}_i^2 \end{equation}\]The \(2^{nd}\) derivatives \(\mathbf{h}_{kk}\) are calculated by modifying the backpropogation rule. Since \(\vec{z}_i = f(\vec{a}_i)\)and $\vec{a}i = \sum{j} \mathbf{w}{ij} \vec{z}_j\(, then by substitution\)\frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{w}^2{ij}} = \frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}^2_{ij}}z_j\(and they further express the\)2^{nd}$$ derivative of the activation output as,

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial a^2_{i}} = f'(\vec{a}_i)^2 - \sum_l \mathbf{w}_{li}^2 \frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec{a}^2_{l}} - f''(\vec{a}_i)^2 \frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec{z}_i^2} \end{equation}\]The derivative of the mean squared error with respect to the to the last linear layer output is then

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec{a}^2_{i}} = 2 f'(\vec{a}_i)^2 - 2(\vec{y}_i - \vec{z}_i)f''(\vec{a}_i) \end{equation}\]The importance of weight \(w_i\) is then \(s_k \approx h_{kk} \vec{w}^2_k /2 \\) and the portion of weights with lowest \(s_k\) are iteratively pruned during retraining.

Optimal Brain Surgeon

% Unlike OBD, \(\mathbf{H}\) or \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\) does not need to be diagonal when computing the loss \(L_q\) to decide the \textit{saliency} of weight \(w_q\).

~\citet{hassibi1994optimal} improve over OBD by preserving the off diagonal values of the Hessian, showing empirically that these terms are actually important for pruning and assuming a diagonal Hessian hurts pruning accuracy.

To make this Hessian computation feasible, they exploit the recursive relation for calculating the inverse hessian \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\) from training data and the structural information of the network. Moreover, using \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\) has advantages over OBD in that it does require further re-training post-pruning. They denote a weight to be eliminated as \(w_q = 0,\ \delta w_q + w_q =0\) with the objective to minimize the following objective:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:obs_2} \min_q \Big\{ \min_{\delta \vec{w}} \{ \frac{1}{2} \delta \vec{w}^T \cdot \mathbf{H} \cdot \delta \vec{w} \} \quad s.t \quad \vec{e}^T_q \cdot \vec{w} + \vec{w}_q = 0 \Big\} \end{equation}\]where $\vec{e}_q\(is the unit vector in parameter space corresponding to parameter\)w_q$$. To solve \autoref{eq:obs_3} they form a Lagrangian from \autoref{eq:obs_2}:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:obs_3} \mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} \delta \vec{w}^T \cdot \mathbf{H} \cdot \delta \vec{w} + \lambda (\vec{e}^T_q \cdot \delta_{\vec{w}} + \vec{w}_q) \end{equation}\]where \(\lambda\)is a Lagrange undetermined multiplier. The functional derivatives are taken and the constraints of \autoref{eq:obs_2} are applied. Finally, matrix inversion is used to find the optimal weight change and resulting change in error is expressed as,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:obs_4} \delta \vec{w} = \frac{w_q}{[\mathbf{H}^{-1}_{qq}]} \mathbf{H}^{-1} \vec{e}_q \quad \text{and} \quad \mathcal{L}_q = \frac{1}{2} \frac{w_q^2}{[\mathbf{H}^{-1}_{qq}]} \end{equation}\]Defining the first derivative as \(\mathbf{X}_k := \frac{f(\vec{x}; \mathbf{W})}{\partial \mathbf{W}}\) the Hessian is expressed as,

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{H} = \frac{1}{P} \sum_{k=1}^{P}\sum_{j=1}^{n} \mathbf{X}_{k,j} \cdot \mathbf{X}_{k,j}^T \end{equation}\]for an \(n\)-dimensional output and \(P\) samples. This can be viewed as the sample covariance of the gradient and \(\mathbf{H}\) can be recursively computed as,

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{H}_{m+1}^{-1} = \mathbf{H}_{m}^{-1} + \frac{1}{P} \mathbf{X}_{m+1}^T \cdot \mathbf{X}_{m+1}^T \end{equation}\]where \(\mathbf{H}_0 = \alpha \mathbf{I}\) and \(\mathbf{H}_P = \mathbf{H}\). Here \(10^{-8 }\leq \alpha \geq 10^{-4}\) is necessary to make \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\) less sensitive to the initial conditions. For OBS, \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\) is required and to obtain it they use a matrix inversion formula ~\citep{kailath1980linear} which leads to the following update:

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{H}^{-1}_{m+1} = \mathbf{H}^{-1}_{m} -\frac{\mathbf{H}^{-1}_{m} \cdot \mathbf{X}_{m+1} \cdot \ \mathbf{X}_{m+1}^T \cdot \mathbf{H}^{-1}_{m}}{ P + \mathbf{X}_{m+1}^{-1} \cdot \mathbf{H}^{-1}_{m} \cdot \mathbf{X}_{m+1}} \quad \text{where} \quad \mathbf{H}_0 = \alpha \mathbf{I}, \quad \mathbf{H}_P = \mathbf{H} \end{equation}\]This recursion step is then used as apart of \autoref{eq:obs_4}, can be computed in one pass of the training data \(1 \leq m \leq P\)and computational complexity of $\mathbf{H}\(remains the same as\)\mathbf{H}^{-1}\(as $\mathcal{O}(P n^2)\). ~\citet{hassibi1994optimal} have also extended their work on approximating the inverse hessian~\citep{hassibi1993second} to show that this approximation works for any twice differentiable objective (not only constrained to sum of squared errors) using the Fisher's score.

Other methods to Hessian approximation include dividing the network into subsets to use block diagonal approximations and eigen decomposition of $\mathbf{H}^{-1}$~\citep{hassibi1994optimal} and principal components of \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}\)~\citep{levin1994fast} (unlike aforementioned approximations,~\citet{levin1994fast} do not require the network to be trained to a local minimum). However the main drawback is that the Hessian is relatively expensive to compute for these methods, including OBD. For \(n\) weights, the Hessian requires \(\mathcal{O}(n^2/2)\) elements to store and performs \(\mathcal{O}(P n^2)\) calculations per pruning step, where \(P\) is total number of pruning steps.

Pruning using First Order Derivatives

As \(2^{nd}\)order derivatives are expensive to compute and the aforementioned approximations may be insufficient in representing the full Hessian, other work has focused on using \(1^{st}\)order information as an alternative approximation to inform the pruning criterion.

~\citet{molchanov2016pruning} use a Taylor expansion (TE) as a criterion to prune by choosing a subset of weights \(W_s\)which have a minimal change on the cost function. They also add a regularization term that explicitly regularize the computational complexity of the network. \autoref{eq:ts_cost} shows how the absolute cost difference between the original network cost with weights \(w\) and the pruned network with \(w'\) weights is minimized such that the number of parameters are decreased where \(||\cdot||_0\) denotes the $0$-norm bounds the number of non-zero parameters \(W_s\).

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:ts_cost} \min_{\mathbf{W}'} |\mathcal{C}(D|\mathbf{W}') - \mathcal{C}(D|\mathbf{W})| \quad \text{s.t.} \quad |\mathbf{W}'|_{0} \leq \mathbf{W}_s \end{equation}\]| Unlike OBD, they keep the absolute change $$ | y | \(resulting from pruning, as the variance\)\sigma^2_y\(is non-zero and correlated with stability of the $\partial C / \partial h\)throughout training, where $\vec{h}$$is the activation of the hidden layer. Under the assumption that samples are independent and identically distributed, $\mathbb{E}( | y | ) =\sigma\sqrt{2}/\sqrt{\pi}\(where $\sigma\)is the standard deviation of $y$, known as the expected value of the half-normal distribution. So, while $y$$tends to zero, the expectation of $ | y | $$is proportional to the variance of $y$, a value which is empirically more informative as a pruning criterion. |

| They rank the order of filters pruned using the TE criterion and compare to an oracle rank (i.e the best ranking for removing pruned filters) and find that it has higher spearman correlation to the oracle when compared against other ranking schemes. This can also be used to choose which filters should be transferred to a target task model. They compute the importance of neurons or filters $z\(by estimating the mutual information with target variable MI$(z;y)\)using information gain $IG(y | z) = \mathcal{H}(z) + \mathcal{H}(y) - \mathcal{H}(z, y)\(where $\mathcal{H}(z)\)is the entropy of the variable $z$, which is quantized to make this estimation tractable. |

Fisher Pruning}

~\citet{theis2018faster} extend the work of~\citet{molchanov2016pruning} by motivating the pruning scheme and providing computational cost estimates for pruning as adjacent layers are successively being pruned. Unlike OBD and OBS, they use, fisher pruning as it is more efficient since the gradient information is already computed during the backward pass. Hence, this pruning technique uses $1^{st}\(order information given by the $2^{nd}\)TE term that approximates the loss with respect to $w$. The fisher information is then computed during backpropogation and uses as the pruning criterion.

The gradient can be formulated as \autoref{eq:fisher_1}, where \(\mathcal{L}(w) = \mathbb{E}_{P}[-\log Q_{\vec{w}}(y | \vec{x})\]\), $d\(represents a change in parameters,\)P\(is the underlying distribution,\)Q_{w}(y | x)\(is the posterior from the model $H\)is the Hessian matrix.

\[\begin{align}\label{eq:fisher_1} g = \nabla \mathcal{L}(w), \quad \mathbf{H} = \nabla^{2}\mathcal{L}(w), \quad \mathcal{L}(w + d) - \mathcal{L}(w) \approx \vec{g}^{T} d + \frac{1}{2} \vec{d}^T \mathbf{H} \vec{d} \\ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{W} - \mathbf{W}_k \vec{e}_i) - \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{W}) + \beta \cdot (C(W - \mathbf{W}_k \vec{e}_i) - C(\mathbf{W})) \end{align}\]Piggyback Pruning

~\citet{mallya2018piggyback} propose a dyanmic masking (i.e pruning) strategy whereby a mask is learned to adapt a dense network to a sparse subnetwork for a specific target task. The backward pass for binary mask is expressed as,

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial m_{ji}} =\Big(\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \hat{y}_j}\Big)\cdot \Big(\frac{\partial y_j}{\partial m_{ji}}\Big) =\partial \hat{y}_j \cdot w_{ji} \cdot x_i, \end{equation}\]where \(m_{ij}\)is an entry in the mask \(m\), \(\mathcal{L}\) is the loss function and $\hat{y}_j\(is the prediction when the $j-th\)mask is applied to the weights $w$. The matrix $m\(can then be expressed as\)\frac{\partial L}{\partial m} = (\delta \vec{y} \cdot \vec{x}^T) \mathbf{W}\(. Note that although the threshold for the mask\)m\(is non-differentiable, but they perform a backward pass anyway. The justification is that the gradients of $m\)act as a noisy estimate of the gradients of the real-valued mask weights $m_r$. For every new task, $m$$is tuned with a new final linear layer.

Structured Pruning

Since standard pruning leads to non-structured connectivity, structured pruning can be used to reduce speed and memory since hardware is more amenable to dealing with dense matrix multiplications, with little to no non-zero entries in matrices and tensors. CNNs in particular are suitable for this type of pruning since they are made up of sparse connections. Hence, below we describe some work that use group-wise regularizers, structured variational, Adversarial Bayesian methods to achieve structured pruning in CNNs.

Structured Pruning via Weight Regularization

%This approach is similar to pruning weights with the smallest indivdual weight magnitude,

Group Sparsity Regularization

Group sparse regularizers enforce a subset of weight groupings, such as filters in CNNs, to be close to zero when trained using stochastic gradient descent. Consider a convolutional kernel represented as a tensor \(K(i, j, s, :)\), the group-wise \(\ell_2,1\)-norm is given as

\[\begin{equation} \omega_{2,1}(K) = \lambda \sum_{i,j,s}||\Gamma_{ijs}|| = \lambda \sum_{ijs} \sqrt{\sum_{t=1}^{T} K(i, j, s, t)^2} \end{equation}\]where \(\Gamma_{ijs}\)is the group of kernel tensor entries \(K(i, j, s, :)\) where \((i,j)\) are the pixel of \(i\)-th row and \(j\)-th column of the image for the \(s\)-th input feature map. This regularization term forces some \(\Gamma_{ijs}\) groups to be close to zero, which can be removed during retraining depending on the amount of compression that the practitioner predefines.

Structured Sparsity Learning

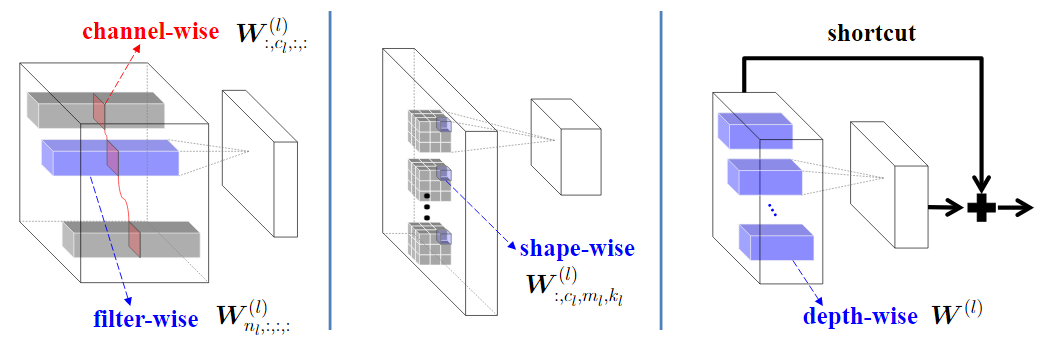

~\citet{wen2016learning} show that their proposed structural regularization can reduce a ResNet architecture with 20 layers to 18 with 1.35 percentage point accuracy increase on CIFAR-10, which is even higher than the larger 32 layer ResNet architecture. They use a group lasso regularization to remove whole filters, across channels, shape and depth as shown in \autoref{fig:ssl}.

\autoref{eq:ssl} shows the loss to be optimized to remove unimportant filters and channels, where \(\mathbf{W}(l)_{n_l,c_l,:,:}\) is the \(c\)-th channel of the \(l\)-th filter for a collection of all weights \(\mathbf{W}\) and \(||\cdot||\) is the group Lasso regularization term where \(||\vec{w}^{(g)} ||_g = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{|\vec{w}^{(g)}|} \big(\vec{w}^{(g)}\big)^2}\)and $|\vec{w}^{(g)}|\(is the number of weights in\)\vec{w}^{(g)}$$.

Since zeroing out the \(l\)-th filter leads to the feature map output being redundant, it results in the \(l+1\) channel being zeroed as well. Hence, structured sparsity learning is carried out for both filters and channels simultaneously.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:ssl} \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{W}) = \mathcal{L}_D(\mathbf{W}) + \lambda_n \cdot \sum_{l=1}^{L}\Big( \sum_{n_l = 1}^N ||\mathbf{W}^{(l)}_{m_l,:,:,:}||_g \Big) + \lambda_c \cdot \sum_{l=1}^{L} \Big(\sum_{c_l = 1}^{C_l} ||\mathbf{W}^{(l)}_{c_l,:,:,:}||_g \Big) \end{equation}\]Structured Pruning via Loss Sensitivity

Structured Brain Damage

The aforementioned OBD has also been extended to remove groups of weights using group-wise sparse regularizers (GWSR)~\citet{lebedev2016fast}. In the case of filters in CNNs, this results in smaller reshaped matrices, leading to smaller and faster CNNs. The GWSR is added as a regularization term during retraining a pretrained CNN and after a set number of epochs, the groups with smallest $\ell_2\(norm are deleted and the number of groups are predefined as\)\tau \in [0, 1]\((a percentage of the size of the network). However, they find that when choosing a value for\)\tau\(, it is difficult to set the regularization influence term\)\lambda\(and can be time consuming manually tuning it. Moreover when $\tau\)is small, the regularization strength of \(\lambda\) is found to be too heavy, leading to many weight groups being biased towards 0 but not being very close to it. This results in poor performance as it becomes more unclear what groups should be removed. However, the drop in accuracy due to this can be remedied by further retraining after performing OBD. Hence, retraining occurs on the sparse network without using the GWSR.

Sparse Bayesian Priors

Sparse Variational Dropout

Seminal work, such as the aforementioned Skeletonization~\citep{mozer1989skeletonization} technique has essentially tried to learn weight saliency. Variational dropout (VD), or more specifically Sparse Variational Dropout~\citep[(SpVD)][]{molchanov2017variational}, learn individual dropout rates for each parameter in the network using varitaional inference (VI). In Sparse VI, sparse regularization is used to force activations with high dropout rates (unlike the original VD~\citep{kingma2015variational} where dropout rates are bound at 0.5) to go to 1 leading to their removal. Much like other sparse Bayes learning algorithms, VD exhibits the Automatic relevance determination (ARD) effect\footnote{Automatic relevance determination provides a data-dependent prior distribution to prune away redundant features in the overparameterized regime i.e more features than samples}. ~\citet{molchanov2017variational} propose a new approximation to the KL-divergence term in the VD objective and also introduce a way to reduce variance in the gradient estimator which leads to faster convergence. VI is performed by minimizing the bound between the variational Gaussian prior \(q_{\phi}(w)\) and prior over the weight \(p(w)\) as,

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\phi) = \max_{\phi} \mathcal{L}_{D} - D_{\text{KL}}\Big(q_{\phi}(w) || p(w)\Big) \quad \text{where} \quad \mathcal{L}_{D}(\phi) = \sum_{n=1}^{N}\mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(w)}\Big[\log p(y_n | \vec{x}_n, \vec{w}_n)\Big] \end{equation}\]They use the reparameterization trick to reduce variance in the gradient estimator when \(\alpha > 0.5\) by replacing multiplicative noise \(1 + \sqrt{\alpha_{ij}} \cdot \epsilon_{ij}\) with additive noise \(\sigma_{ij} \cdot \epsilon_{ij}\), where \(\epsilon_{ij} \sim \mathcal{N}(0;1)\) and \(\sigma^2_{ij}=\alpha_{ij}\cdot \theta^2_{ij}\) is tuned by optimizing the variational lower bound w.r.t \(\theta\) and \(\sigma\). This difference with the original VD allow weights with high dropout rates to be removed.

Since the prior and approximate posterior are fully factorized, the full KL-divergence term in the lower bound is decomposed into a sum:

\[\begin{equation} D_{\text{KL}}(q(\mathbf{W}|\theta, \alpha)|| p(\mathbf{W})) = \sum_{ij} D_{\text{KL}}(q(w_{ij} | \theta_{ij}, \alpha_{ij}) || p(w_{ij})) \end{equation}\]Since the uniform log-prior is an improper prior, the KL divergence is only computed up to an additional constant~\citep{kingma2015variational}.

\[\begin{equation} - D_{\text{KL}}(q(w_{ij}|\theta_{ij}, \alpha_{ij}) || p(w_{ij})) =\frac{1}{2}\log \alpha_{ij} - E \sim N(1, \alpha_{ij})\log |\cdot|+ C \end{equation}\]In the VD model this term is intractable, as the expectation \(E \sim N(1,\alpha_{ij}) \log |\cdot|_in\) cannot be computed analytically~\citep{kingma2015variational}. Hence, they approximate the negative KL. The negative KL increases as \(\alpha_{ij}\) increases which means the regularization term prefers large values of $\alpha_{ij}\(and so the correspond weight $w_{ij}\)is dropped from the model. Since using SVD at the start of training tends to drop too many weights early since the weights are randomly initialized, SVD is used after an initial pretraining stage and hence this is why we consider it a pruning technique.

Bayesian Structured Pruning

Structured pruning has also been achieved from a Bayesian view~\citep{louizos2017bayesian} of learning dropout rates. Sparsity inducing hierarchical priors are placed over the units of a DNN and those units with high dropout rates are pruned. Pruning by unit is more efficient from a hardware perspective than pruning weights as the latter requires priors for each individual weight, being far more computationally expensive and has the benefit of being more efficient from a hardware perspective as whole groups of weights are removed.

If we consider a DNN as \(p(D|w) =\prod_{i=1}^{N}p(y_i|x_i,w)\) where \(x_i\) is a given input sample with a corresponding target \(y_i\), $w\(are the weights of the network, governed by a prior distribution\)p(w)\(. Since computing the posterior\)p(w|D) = p(D|w)p(w)/p(D)\(explicitly is intractactble,\)p(w)\(is approximated with a simpler distribution, such as a Gaussian\)q(w)\(, parameterized by variational parameters\)\phi$$. The variational parameters are then optimized as,

\[\begin{gather}\label{eq:elbo} \mathcal{L}_E = \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(w)}[\log p(D|w)], \quad \mathcal{L}_C = \mathbb{E}_{q_{\phi}(w)}[\log p(w)] +\mathcal{H}(q_{\phi}(w)) \\ L(\phi) = \mathcal{L}_E + \mathcal{L}_C \end{gather}\]where \(\mathcal{H}(\cdot)\) denotes the entropy and \(\mathcal{L}(\phi)\) is known as the evidence-lower-bound (ELBO). They note that $\mathcal{L}_E\(is intractable for noisy weights and in practice Monte Carlo integration is used. When the simpler $q_{\phi}(w)\)is continuous the reparameterization trick is used to backpropograte through the deterministic part $\phi\(and Gaussian noise\)\epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2 I)\(. By substituting this into \autoref{eq:elbo} and using the local reparameterization trick~\citep{kingma2015variational} they can express $\mathcal{L}(\phi)\)as

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\phi) = \mathbb{E}_p(\epsilon)[\log p(D|f(\phi, \epsilon))] + \mathbb{E}_{q_{\epsilon(w)}}[\log p(w)] + \mathcal{H}(q_{\phi(w)}), \quad \text{s.t} \quad w=f(\phi, \epsilon) \end{equation}\]with unbiased stochastic gradient estimates of the ELBO w.r.t the variational parameters $\phi$. They use mixture of a log-uniform prior and a half-Cauchy prior for $p(w)\(which equates to a horseshoe distribution~\citep{carvalho2010horseshoe}. By minimizing the negative KL divergence between the normal-Jeffreys scale prior $p(z)\)and the Gaussian variational posterior \(q_{\phi}(z)\) they can learn the dropout rate \(\alpha_i= \sigma^2 z_i/\mu_2 z_i\) as

\begin{equation} -D_{\text{KL}}(\phi(z)||p(z)) \approx A \sum_i(k_1 \sigma(k_2 + k_3 \log \alpha_i) - 0.5 m(- \log \alpha_i) - k_1) \end{equation}

where $\sigma(\cdot)\(is the sigmoid function, $m(\cdot)\) is the softplus function and \(k_1 = 0.64\), \(k_2= 1.87\) and \(k_3= 1.49\). A unit \(i\) is pruned if its variational dropout rate does not exceed threshold \(t\), as \(\log \alpha_i= (\log \sigma^2 zi - \log \mu_2 z_i) \geq t\).

It should be mentioned that this prior parametrization readily allows for a more flexible marginal posterior over the weights as we now have a compound distribution,

\[\begin{equation} q_{\phi}(W) = \int q_{\phi}(W|z) q_{\phi}(z) dz \end{equation}\]Pruning via Variational Information Bottleneck}

~\citet{dai2018compressing} minimize the variational lower bound (VLB) to reduce the redundancy between adjacent layers by penalizing their mutual information to ensure each layer contains useful and distinct information. A subset of neurons are kept while the remaining neurons are forced toward 0 using sparse regularization that occurs as apart of their variational information bottleneck (VIB) framework. They show that the sparsity inducing regularization has advantages over previous sparsity regularization approaches for network pruning.

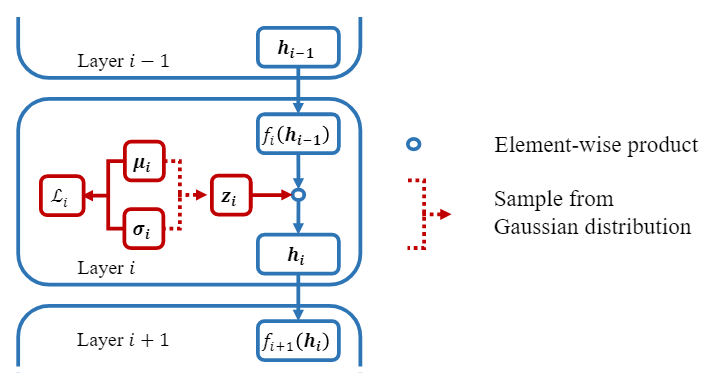

\autoref{eq:vib} shows the objective for compressing neurons (or filters in CNNs) where $\gamma_i\(controls the amount of compression for the $i$-th layer and $L\)is a weight on the data term that is used to ensure that for deeper networks the sum of KL factors does not result in the log likelihood term outweighed when finding the globally optimal solution.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:vib} \mathcal{L}= \sum_{i=1}^L \gamma_i \sum_{j=1}^{r_i} \log \Big( 1 +\frac{\mu^2_{i,j}}{ \sigma^2_{i,j}} \Big) - L \mathbb{E}_{\{\vec{x},y\}\sim D,\ \vec{h} \sim p(\vec{h}|\vec{x})}\Big[\log q(\vec{y}|\vec{h}_L) \Big] \end{equation}\]\(L\) naturally arises from the VIB formulation unlike probabilistic networks models. The \(\log(1 + u)\) in the KL term is concave and non-decreasing for range \([0, \infty]\) and therefore favors solutions that are sparse with a subset of parameters exactly zero instead of many shrunken ratios \(\alpha_{i,j}: \mu^2_{i,j} \sigma^{-2}_{i,j}, \ \forall i,j\).

Each layer is sampled \(\epsilon_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I)\) in the forward pass and \(\vec{h}_i\) is computed. Then the gradients are updated after backpropogation for \(\{\mu_i, \sigma_i \mathbf{W}_i \}^L_{i=1}\) and output weights \(\mathbf{W}_y\).

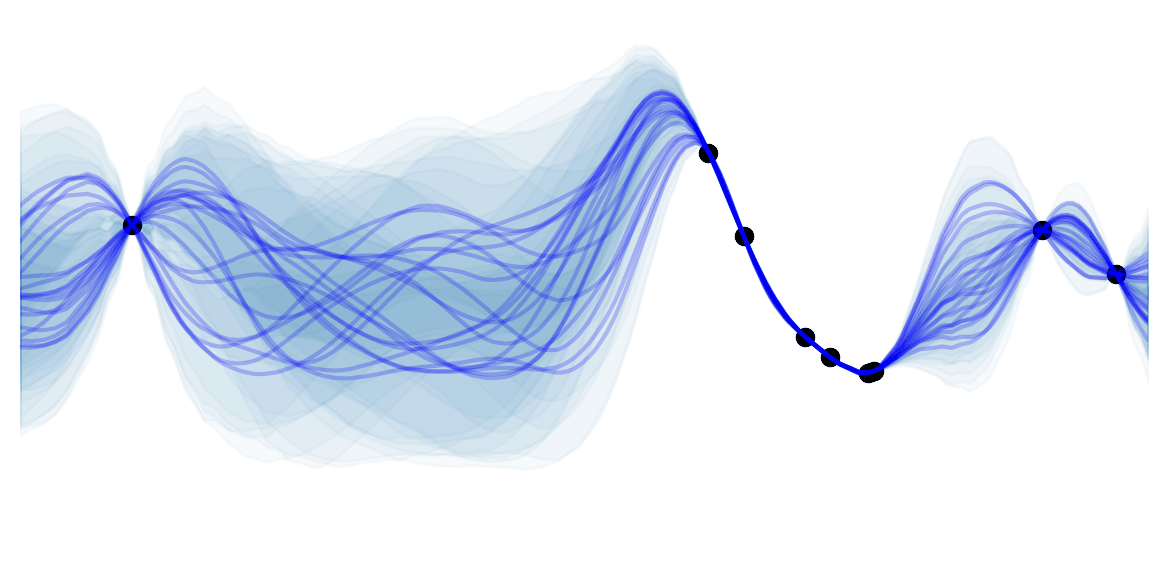

\autoref{fig:vib} shows the conditional distribution \(p(\vec{h}_i|\vec{h}_{i-1})\) and \(\vec{h}_{i}\) sampled by multiplying \(f_i(\vec{h}_{i-1})\) with a random variable \(\vec{z}_i := \mu_i+ \epsilon_i \circ \sigma_i\).

They show that when using VIB network, the mutual information increases between \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{h}_1\) as it initially begins to learn and later in training the mutual information begins to drop as the model enters the compression phase. In constrast, the mututal information for the original stayed consistently high tending towards 1.

Generative Adversarial-based Structured Pruning}

~\citet{lin2019towards} extend beyond pruning well-defined structures, such as filters, to more general structures which may not be predefined in the network architecture. They do so applying a soft mask to the output of each structure in a network to be pruned and minimize the mean squared error with a baseline network and also a minimax objective between the outputs of the baseline and pruned network where a discriminator network tries to distinguish between both outputs. During retraining, soft mask weights are learned over each structure (i.e filters, channels, ) with a sparse regularization term (namely, a fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm) to force a subset of the weights of each structure to go to 0. Those structures which have corresponding soft mask weight lower than a predefined threshold are then removed throughout the adversarial learning. This soft masking scheme is motivated by previous work~\citep{lin2018accelerating} that instead used hard thresholding using binary masks, which results in harder optimization due to non-smootheness. Although they claim that this sparse masking can be performed with label-free data and transfer to other domains with no supervision, the method is largely dependent on the baseline (i.e teacher network) which implicitly provides labels as it is trained with supervision, and thus it pruned network transferability is largely dependent on this.

Search-based Pruning}

Search-based techniques can be used to search the combinatorial subset of weights to preserve in DNNs. Here we include pruning techniques that don't rely on gradient-based learning but also evolutionary algorithms and SMC methods.

Evolutionary-Based Pruning}

Pruning using Genetic Algorithms}

The basic procedure for Genetic Algorithms (GAs) in the context of DNNs is as follows; (1) generate populations of parameters (or \textit{chromosones} which are binary strings), (2) keep the top-k parameters that perform the best (referred to as tournament selection) according to a predefined \textit{fitness} function (e.g classification accuracy), (3) randomly mix (i.e cross over) between the parameters of different sets within the top-k and perturb a portion of the resulting parameters (i.e mutation) and (4) repeat this procedure until convergence. This procedure can be used to find a subset of the DNN network that performs well.

~\citet{whitley1990genetic} use a GA to find the optimal set of weights which involves connecting and reconnecting weights to find mutations that lead to the highest fitness (i.e lowest loss). They define the number of backpropogation steps as \(ND + B\) where \(B\) is the baseline number of steps, $N\(is the number of weights pruned and\)D$$ is the increase in number of backpropgation steps. Hence, if the network is heavily pruned the network is allocated more retraining steps. Unlike standard pruning techniques, weights can be reintroduced if they are apart of combination that leads to a relatively good fitness score. They assign higher reward to network which more heavily pruned, otherwise referred to as \textit{selective pressure} in the context of genetic algorithms.

Since the cross-over operation is not specific to the task by default, interference can occur among related parameters in the population which makes it difficult to find a near optimal solution, unless the population is very large (i.e exponential with respect to the number of features).~\citet{cantu2003pruning} identify the relationship between variables by computing the joint distribution of individuals left after tournament selection and use this sub-population to generate new members of the population for the next iteration. This is achieved using 3 distribution estimation algorithms (DEA). They find that DEAs can improve GA-based pruning and that in pruned networks using GA-based pruning results in faster inference with little to no difference in performance compared to the original network.

Recently,~\citet{hu2018novel} have pruned channels from a pretrained CNN using GAs and performed knowledge distillation on the pruned network. A kernel is converted to a binary string $K\(with a length equal to the number of channels for that kernel. Then each channel is encoded as 0 or 1 where channels with a 0 are pruned and the n-th kernel\)K_n\(is represented a a binary series after sampling each bit from a Bernoulli distribution for all\)C\(channels. Each member (i.e channels) in the population is evaluated and top-k are kept for the next generation (i.e iteration) based on the fitness score where k corresponds to the total amount of pruning. The Roulette Wheel algorithm is used as the selection strategy~\citep{goldberg1991comparative} whereby the\)n\(-th member of the $m$-th generation\)I_{m,n}$$ has a probability of selection proportional to its fitness relative to all other members. This can simply be implemented by inputting all fitness scores for all members into a softmax. To avoid members with high fitness scores losing information post mutation and cross-over, they also copy the highest fitness scoring members to the next generation along with their mutated versions.

The main contribution is a 2-stage fitness scoring process. First, a local TS approximation of a layer-wise error function using the aforementioned OBS objective~\citep{dong2017learning} (recall that OBS mainly revolves around efficient Hessian approximation) is used sequentially from the first layer to the last, followed by a few epochs of retraining to restore the accuracy of the pruned network. Second, the pruned network is distilled usin a cross-entropy loss and regularization term that forces the features maps of the pruned network to be similar to the distilled model, using an attention map to ensure both corresponding layer feature maps are of the same and fixed size. They achieve SoTA on ImageNet and CIFAR-10 for VGG-16 and ResNet CNN architectures using this approach.

% Given that particle filters and genetic algorithms bare some relation~\citep{kwok2005evolutionary}, we conjecture that there may be some connection to the pruning technique by ~\citet{anwar2017structured}.

Pruning via Simulated Annlealing}

~\citet{noy2019asap} propose to reduce search time for searching neural architectures by relaxing the discrete search to continuous that allows for a differentiable simulated annealing that is optimized using gradient descent (following from the DARTS~\citep{liu2018darts} approach). This leads to much faster solutions compared to using black-box search since optimizing over the continuous search space is an easier combinatorial optimization problem that in turn leads to faster convergence. This pruning technique is not strictly consider compression in its standard definition, as it prunes during the initial training period as opposed to pruning after pretraining. This falls under the category of neural architecture search (NAS) and here they use an annealing schedule that controls the amount of pruning during NAS to incrementally make it easier to search for sub-modules that are found to have good performance in the search process. Their (0, $\delta$)-PAC theorem guarantees under few assumptions (see paper for further details on these assumptions) that this anneal and prune approach prunes less important weights with high probability.

Sequential Monte Carlo \& Reinforcement Learning Based Pruning}

Particle Filter Based Pruning}

~\citet{anwar2017structured} identifies important weights and paths using particle filters where the importance weight of each particle is assigned based on the misclassification rate with corresponding connectivity pattern. Particle filtering (PF) applies sequential Monte Carlo estimation with particle representing the probability density where the posterior is estimated with a random sample and parameters that are used for posterior estimation. PF propogates parameters with large magnitudes and deletes parameters with the smallest weight in re-sampling process, similar to MBP. They use PF to prune the network and retrain to compensate for the loss in performance due to PF pruning. When applied to CNNs, they reduce the size of kernel and feature map tensors while maintaining test accuracy.

Particle Swarm Optimized Pruning}

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has also been combined with correlation merging algorithm (CMA) for pruning~\citep{tu2010neural}. \autoref{eq:pso} shows the PSO update formula where the velocity $\mathbf{V}_{id}\(for i-th position of particle $\mathbf{X}_id\)(i.e a parameter vector in a DNN) at the $d$-th iteration,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:pso} \mathbf{V}_{id} := \mathbf{V}_{id} + c_1 u (\vec{P}_{id} - \vec{X}_{id}) + c_2 u (\vec{P}_{gd} - \vec{X}_{id}), \quad \text{where} \quad \vec{X}_{id} = \vec{X}_{id} + \mathbf{V}_{id} \end{equation}\]where \(u \sim \text{Uniform}(0, 1)\) and \(c_1, c_2\) are both learning rates, corresponding to the influence social and cognition components of the swarm respectively~\citep{kennedy1995particle}. Once the velocity vectors are updated for the DNN, the standard deviation is computed for the i-th activation as \(s_i = \sum_{p=1}^{n} (\mathbf{V}_{ip} - \bar{\mathbf{V}}_i)^2\)where $\bar{v}_i\(is the mean value of\)\mathbf{V}_i$$ over training samples.

Then compute Pearson correlation coefficient between the \(i\)-th an \(j\)-th unit in the hidden layer as \(\mathbf{C}_{ij} = (\mathbf{V}_{ip} \mathbf{V}_{jp} - n\bar{\mathbf{V}}_i \bar{\mathbf{V}}_j)/\vec{S}_i \vec{S}_j\) and if \(\mathbf{C}_{ij} > \tau_1\) where \(\tau\) is a predefined threshold, then merge both units, delete the j-th unit and update the weights as,

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{W}_{ki} = \mathbf{W}_{ki} + \alpha \mathbf{W}_{ki} \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{W}_{kb} = \mathbf{W}_{kb} + \beta \mathbf{W}_k \end{equation}\]where,

\[\begin{equation} \alpha = \frac{\mathbf{V}_{ip} \mathbf{V}_{jp} - n\bar{\mathbf{V}}_i \bar{\mathbf{V}}_j}{\sum_{n=1}^p \mathbf{V}_{ip} \mathbf{V}_{jp} - \bar{\mathbf{V}}^{2}_i}, \quad \beta = \bar{\mathbf{V}}_j - \alpha \bar{\mathbf{V}}_i \end{equation}\]and \(\mathbf{W}_{ki}\) connects the last hidden layer to output unit \(k\). If the standard deviation of unit \(i\) is less than \(\tau_2\) then it is combined with the output unit \(k\). Finally, remove unit \(j\) and update the bias of the output unit k as \(\mathbf{W}_{kb}= \mathbf{W}_{kb} + \vec{\bar{V}}_i \mathbf{W}_{ki}\). This process is repeated until a maximally compressed network than maintains performance similar to the original network is found.

Automated Pruning

AutoML~\citep{he2018amc} use RL to improve the efficiency of model compression performance by exploiting the fact that the sparsity of each layer is a strong signal for the overall performance. They search for a compressed architecture in a continuous space instead of searching over a discrete space. A continuous compression ratio control strategy is employed using an actor critic model (Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient~\citep{silver2014deterministic}) which is known to be relatively stable during training, compared to alternative RL models, due lower variance in the gradient estimator. The DDPG processes each consecutive layer, where for the $t$-th layer $L_t$, the network receives a layer embedding $t\(that encodes information of this layer and outputs a compression ratio $a_t\)and repeats this process from the first to last layer. The resulting pruned network is evaluated without fine-tuning, avoiding retraining to improve computational cost and time. During training, they fine-tune best explored model given by the policy search. The MBP ratio is constrained such that the compressed model produced by the agent is below a resource constrained threshold in resource constrained case. Moreover, the maximum amount of pruning for each layer is constrained to be less than 80\%, When the focus is to instead maintain accuracy, they define the reward function to incorporate accuracy and the available hardware resources.

By only requiring 1/4 number of the FLOPS they still manage to achieve a 2.7\% increase in accuracy for MobileNet-V1. This also corresponds to a 1.53 times speed up on a Titan Xp GPU and 1.95 times speed up on Google Pixel 1 Android phone.

Pruning Before Training

Thus far, we have discussed pruning pretrained networks. Recently, the \text{lottery ticket} hypothesis~\citep[LTH][]{frankle2018lottery} showed that there exists sparse subnetworks that when trained from scratch with the same initialized weights can reach the same accuracy as the full network. The process can be formalized as:

- Randomly initialize a neural network \(f(\vec{x}; \theta_0)\)(\text{where} $\theta_0 \sim D_\theta $$).

- Train the network for \(j\) iterations, arriving at parameters \(\theta_j\)

- Prune \(p\)\% of the parameters in \(\theta_j\), creating a mask \(m\).

- Reset the remaining parameters to their values in \(\theta_0\), creating the winning ticket \(f(\vec{x}; m \otimes \theta_0 )\).

~\citet{liu2018rethinking} have further shown that the network architecture itself is more important than the remaining weights after pruning pretrained networks, suggesting pruning is better perceived as an effective architecture search. This coincides with Weight Agnostic Neural Networks~\citep[WANN;][]{gaier2019weight} search which avoids weight training. Topologies of WANNs are searched over by first sampling single shared weight for a small subnetwork and evaluated over several randomly shared weight rollout. For each rollout the cumulative reward over a trial is computed and the population of networks are ranked according to the resulting performance and network complexity. This highest ranked networks are probabilistically selected and mixed at random to form a new population. The process repeats until the desired performance and time complexity is met.

The two aforementioned findings (there exists smaller sparse subnetworks that perform well from scratch and the importance of architecture design) has revived interest in finding criteria for finding sparse and trainable subnetworks that lead to strong performance.

However, the original LTH paper was demonstrated on relatively simpler CV tasks such as MNIST and when scaled up it required careful fine-tuning of the learning rate for the lottery ticket subnetwork to achieve the same performance as the full network. To scale up LTH to larger architectures ~\cite{frankle2019lottery} in a stable way without requiring any additional fine-tuning, they relax the restrictions of reverting to the lottery ticket being found at initialization but instead revert back to the \(k\)-th epoch. This \(k\) typically corresponds to only few training epochs from initialization. Since the lottery ticket (i.e subnetwork) no longer corresponds to a randomly initialized subnetwork but instead a network trained from \(k\) epochs, they refer to these subnetworks as \textit{matching tickets} instead. This relaxation on LTH allows tickets to be found on CIFAR-10 with ResNet-20 and ImageNet with ResNet-50, avoiding the need for using optimizer warmups to precompute learning rate statistics.

~\citet{zhou2019deconstructing} have further investigate the importance of the three main factors in pruning from scratch: (1) the pruning criteria used, (2) where the model is pruned from (e.g from initialization or \(k\)-th epoch) and (3) the type of mask used. They find that the measuring the distance between the weight value at intialization and its value after training is a suitable criterion for pruning and performs at least as well as preserving weights based on the largest magnitude. They also note that if the sign is the same after training, these weights can be preserved. Lastly, they find for (3) that using a binary mask and setting weights to 0 is plays an integral part in LTH. Given that these LTH based pruning masks outperform random masks at initialization, leads to the question whether we can search for architectures by pruning as a way of learning instead of traditional backpropogation training. In fact,~\cite{zhou2019deconstructing} have also propose to use REINFORCE~\citep{sutton2000policy} to optimize and search for optimal wirings at each layer. In the next subsection, we discuss recent work that aims to find optimal architectures using various criteria.

Pruning to Search for Optimal Architectures

Before LTH and the aforementioned line of work, Deep Rewiring~\citep[DeepR;][]{bellec2017deep} was proposed to adaptively prune and reappear periodically during training by drawing stochastic samples of network configurations from a posterior. The update rule for all active connections is given as,

\[\begin{equation} \mathbf{W}_k \gets \mathbf{W}_k - \eta \frac{\partial E}{\partial \mathbf{W}_k}- \eta \alpha + \sqrt{2 \eta \Gamma} v_k \end{equation}\]for \(k\)-th connection. Here, $\eta\(is the learning rate, $\Gamma\)is a temperature term, \(E\) is the error function and the noise \(v_k \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I\sigma^{2})\)for each active weight \(\mathbf{W}\). If the \(\mathbf{W}_k < 0\) then the connection is frozen. When the set the number of dormant weights exceeds a threshold, they reactivate dormant weights with uniform probability. The main difference between this update rule and SGD lies in the noise term \(\sqrt{2 \eta \Gamma} v_k\) whereby the \(v_k\) noise and the amount of it controlled by \(\Gamma\) performs a type of random walk in the parameter space. Although unique, this approach is computationally expensive and challenging to apply to large networks and datasets.

Sparse evolutionary training~\citep[SET;][]{mocanu2018scalable} simplifies prune–regrowth cycles by replacing the top-\(k\) lowest magnitude weights with newly randomly initialized weights and retrains and this process is repeated throughout each epoch of training.~\citet{dai2019nest} carry out the same SET but using gradient magnitude as the criterion for pruning the weights. Dynamic Sparse Reparameterization~\citep[DSR;][]{mostafa2019parameter} implements a prune–redistribute–regrowth cycle where target sparsity levels are redistributed among layers, based on loss gradients (in contrast to SET, which uses fixed, manually configured, sparsity levels). SparseMomentum~\citep[SM;][]{dettmers2019sparse} follows the same cycle but instead using the mean momentum magnitude of each layer during the redistribute phase. SM outperforms DSR on ImageNet for unstructured pruning by a small margin but has no performance difference on CIFAR experiments. Our approach also falls in the dynamic category but we use error compensation mechanisms instead of hand crafted redistribute–regrowth cycles.

~\citet{ramanujan2020s}\footnote{This approach also is also relevant to \autoref{sec:pufod} as it relies on \(1^{st}\) order derivatives for pruning. propose an \texttt{edge-popup} algorithm to optimize towards a pruned subnetwork from a randomly initialized network that leads to optimal accuracy. The algorithm works by switching edges until the optimal configuration is found. Each weight is assigned a ``popup'' score \(s_{uv}\) from neuron \(u\) to \(v\). The top-\(k\) \% percentage of weights with the highest popup score are preserved while the remaining weights are pruned. Since the top-k threshold is a step function which is non-differentiable, they propose to use a straight-through estimator to allow gradients to backpropogate and differentiate the loss with respect to \(s_{uv}\) for each respective weight i.e the activation function \(g\) is treated as the identity function in the backward pass. The scores \(s_{uv}\) are then updated via SGD. Unlike,~\citet{theis2018faster} that use the absolute value of the gradient, they find that preserving the direction of momentum leads to better performance. During training, removed edges that are not within the top-k can switch to other positions of the same layer as the scores change. They show that this shuffling of weights to find optimal permutation leads to lower cross-entropy loss throughout training. Interestingly, this type of adaptive pruning training leads to competitive performance on ImageNet when compared to ResNet-34 and can be performed on pretrained networks.

Few-Shot and Data-Free Pruning Before Training

Pruning from scratch requires a criterion that when applied, leads to relatively strong out-of-sample performance compared to the full network. LTH established this was possible, but the method to do so requires an intensive number of pruning-retraining steps to find this subnetwork. Recent work, has focused trying to find such subnetworks without any training, of only a few mini-batch iterations. ~\citet{lee2018snip} aim to find these subnetworks in a single shot i.e a single pass over the training data. This is referred to as Single-shot Network Pruning (SNIP) and as in previously mentioned work it too constructs the pruning mask by measuring connection sensitivities and identifying structurally important connections.

~\citet{you2019drawing} identify to as early-bird tickets (i.e winning tickets early on in training) using a combination of early stopping, low-precision training and large learning rates. Unlike, LTH that use unstructured pruning, `early-bird' tickets are identified using structured pruning whereby whole channels are pruned based on their batch normalization scaling factor. Secondly, pruning is performed iteratively within a single training epoch, unlike LTH that performs pruning after numerous retraining steps. The idea of pruning early is motivated by ~\citet{saxe2019information} that describe training in two phase: (1) a label fitting phase where most of the connectivity patterns form and (2) a longer compression phase where the information across the networks is dispersed and lower layers compress the input into more generalizable representations. Therefore, we may only need phase (1) to identify important connectivity patterns and in turn find efficient sparse subnetworks.~\citet{you2019drawing} conclude that this hypothesis in fact the case when identifying channels to be pruned based on the hamming distance between consequtive pruning iterations. Intuitively, if the hamming distance is small and below a predefined threshold, channels are removed.

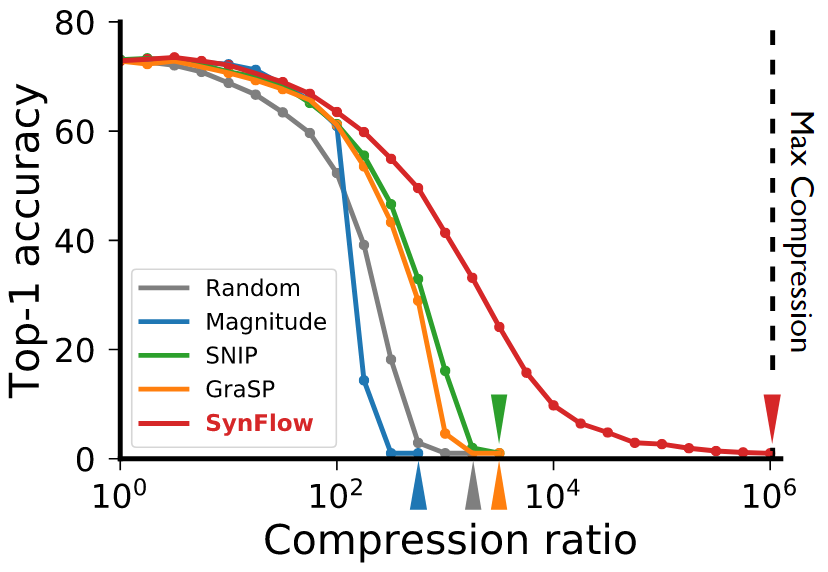

~\citet{tanaka2020pruning} have further investigated whether tickets can be identified without any training data. They note that the main reason for performance degradation with large amounts of pruning is due to \text{layer collapse}. Layer collapse refers when too much pruning leads to a cut-off of the gradient flow (in the extreme case, a whole layer is removed), leading to poor signal propogation and maximal compression while allowing the gradient to flow is referred to as \textit{critical compression}.

They show that retraining with MBP avoids layer-wise collapse because gradient-based optimiziation encourages compression with high signal propogation. From this insight, they propose a measure for measuring synaptic flow, expressed in \autoref{eq:syn_flow}. The parameters are first masked as $\theta_{\mu} \gets \mu \odot \theta_0$. Then the iterative synaptic flow pruning objective is evaluated as,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:syn_flow} \mathcal{L} = \mathbf{1}^{T}(\prod_{l=1}^{T} |\theta[l]_{\mu}|) \mathbf{1} \end{equation}\]where \(\mathbf{1}\)is a vectors of ones. The score \(\mathcal{S}\)is then computed as \(\mathcal{S} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \theta_{\mu}} \odot \theta_{\mu}\) and the threshold \(\tau\) is defined as \(\tau = (1 - \rho - k/n)\) where \(n\) is the number of pruning iterations and \(\rho\) is the compression ratio. If \(\mathcal{S}) > \tau\) then the mask \(\mu\) is updated.

The effects of layer collapse for various random pruning, MBP, SNIP and synaptic flow (SynFlow) are shown in \autoref{fig:syn_flow}. We see that SynFlow achieves far higher compression ratio for the same test accuracy without requiring any data.